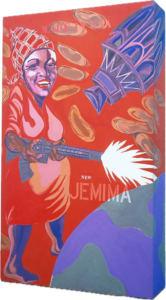

Mammy is a speculative fiction story that you can read below. The piece came to me around the time of my father’s passing. My father, Joe Overstreet, 1933—2019, painted his whole life. While his art was always socially conscious, before immersing himself in Abstract Expressionism, his work was more figurative.

The New Jemima was first painted in 1964, then he recreated it in 1971 as part of a project to desegregate Rice University. The newer version is over eight feet tall and five feet wide. It was a bold statement for the time—and an echo of the era—the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and the women’s movement—all combined into the painting’s theme.

Sixty years later, the saying “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes,” certainly applies.

Joe Overstreet, Artist The New Jemima , 1964, 1971

Joe Overstreet, Artist The New Jemima , 1964, 1971

Medium Acrylic on fabric over plywood construction

Dimensions 102 3/8 x 60 3/4 x 17 1/4 in. (260 x 154.3 x 43.8 cm)

Credit The Menil Collection, Houston. Photo courtesy of the Menil Collection

“With The New Jemima, the artist has transformed the negative—albeit popular—image of a subservient Aunt Jemima into an empowered figure, wielding a machine gun with pancakes flying through the air like bullets.” (The Menil Collection)

Mammy

By J.D. Overstreet

1.

The scratching sound woke Vi. She lay still, listening as wakefulness crept in. Slowly, she sat up, pulling the blankets with her. Vi looked over the loft railing, her eyes locked on the front door. The sound was definitely coming from there. Rats? The building wasn’t that old.

It was then she heard pounding—two, three—followed by a crash. A door burst open—one, maybe two apartments away. Vi’s heart lurched into an uneven rhythm. She threw off the covers, climbed down the loft ladder, and bolted for the door. Holding her breath, she pressed her eye to the peephole. Blurred shapes whipped past in the hallway.

Then a dark figure stepped in front of her door, the peephole nearly covered. She strained to see around the man, then he turned, looking directly at her. Startled, she backed away from the door, listening to what sounded like people moving things. Could someone be moving in or out? That didn’t make much sense—it was the middle of the night. There was a squeal. Was there a dog over there? She had wanted one but was told, under no circumstances, were pets allowed. Then it occurred to her: could that have been a woman? She’d only lived there for three weeks, but Vi had seen a woman in the hall. She heard the man step away from her door and eased to the peephole for another look. The sounds of struggling were already fading down the hall.

She stood frozen in the dark, long after the hallway had cleared. There was no chance she’d sleep again. She left the lights off as she washed her face, made her lunch, and got dressed. She reviewed her notes until it was time. After six months of training, Vi’s first day on the job had finally arrived.

Her new desk was in an old building at the edge of the city. ‘The Comedy of Past Events,’ was a small department in the Ministry of Information, and her department was a tiny part of that. A brightly colored sign identified it.

That morning, new banners flew outside ‘The Comedy’—‘Something old, Something new!’ The flags snapped in the wind. It was the latest slogan that SofTeq-LS had come up with. Post war branding was an essential part of acceptance. Like all the major cities on the West and East Coasts, each had been renamed by SofTeq-LS, a ‘thinking machine language system.’ What was now Frisco-Ana, had once been known only as San Francisco.

The microcar Vi had been assigned was a two-seater—little more than a shell with a computer brain that did the driving. It dropped her off in the back parking lot of The Comedy and plugged itself into the grid below. During training, she discovered that parking in the back and taking the long way around gave her a view of the bay and the gateway leading to the ocean. Vi checked the mirror, gave her hair a final fluff, and smoothed her light blue coat—the uniform that she would wear from that day on. She thought of herself as lucky, having been chosen for her new position.

Vi was lucky, in fact, because her racial purity test proved that her olive skin was not a fluke of nature, but was a product of racial mixing. The new government used the test to assign forced labor details in the ‘Restore America’ program. But she had known the results of her tests before she even took them. She kept a picture of her paternal grandmother taped inside her dresser. She was a large black woman that had a shock of gray going through her natural hair. Vi never met her, but looked at the picture often.

During training, Vi entered the building each day at 6:48. She was determined to beat her old work streak—917 consecutive days, cut short only by what they liked to call “nervous work exhaustion.” That kind of dedication had gotten her noticed. At least, that’s what she told herself. But she suspected she’d been chosen because Dr. Charles—the man from a house she used to clean—had been promoted to a government position.

He had always “liked” her, but the thought of him made Vi’s skin crawl. She received the notice during her seventeen-minute lunch break and could hardly believe it. Luck, divine intervention, Dr. Charles, however it happened didn’t matter. Vi had to read the notice several times—she had been put forward as a potential “Mammy,” an old slave term SofTeq-LS had resurrected when the new administration rebranded welfare agents.

On her first day, Vi was finally allowed to wear the light blue coat all Mammies wore. She’d had it for over a week, but it was illegal to wear in public until training was complete. Now, she donned it with pride. Each morning, before fieldwork began, rows of blue-coated Mammies hunched over their screens.

Because the fertility rate had plummeted below one percent, most Mammies—nine out of ten—were responsible for managing the adult population. They kept society running, ensuring the Restore America program operated without disruption. Acting as truant officers for the labor force, they wielded authority not only to detain but to administer corporal punishment when necessary to maintain order.

New Mammies, like Vi, were assigned to toddlers and newborns—a task she was grateful for. The thought of corralling an unwilling workforce scared her, though she knew her time would come. But as Vi reached her desk, she hesitated and glanced around. No one seemed to notice. A large plastic box sat on her new desk, a note taped to the top.

“It seems this diary and drawings belonged to a pre-adult of seven,” the note read. “It appears they were written in private moments, documenting everything from the routine beatings he’d gotten from his stepfather to major events of the time, such as the assassination of a Dr. Martin Luther King (who, from what I’ve gathered, was actually some sort of priest, not a doctor at all). The documents seemed interesting, but since this era is now considered ‘the time before,’ I wasn’t sure whether to burn them, as required. I’m sure the Comedy of Past Events will know what to do with them. If I find anything else, I will, of course, turn it in as well.”

The note was signed with a scribble.

Vi flipped open the lid and found a jumble of papers and drawings, clearly the work of a child. At the bottom of the box lay a diary. Since it was her first official day on the job, she wasn’t sure if boxes like this showed up regularly or if this was something unusual. She flipped through the diary and found a name printed in shaky, childlike handwriting: Benjamin Underwood. Ben.

Vi had never seen original documents from ‘the time before’ written by a child—at least, what she still considered a child. Since the new administration had streamlined the three branches of government into one, the complications from oversight had disappeared. By decree, anyone between the ages of 4.5 and 13 was classified as a pre-adult and sentenced accordingly. Something about the practice didn’t sit right with Vi, though she’d never said so. She didn’t know anyone that young, but she doubted they had much sense of judgment or control. The law was the law, she reasoned, and people of that age were constantly needed to fill the void in the workforce.

At 7:14, the office bells chimed. The morning message from the Magistrate of Justice began as usual, set against a backdrop of soft piano music. His baritone voice was smooth and measured. Each day, he reminded everyone how lucky they were—since the righteous had won the war and the non-righteous had been subdued, the country had finally stabilized. His breathy voice was both soothing and confident, a steady reassurance. Cameras watched as workers paused, all expected to give the message their full attention.

Vi had grown used to hearing it during training, each day’s message blending into the next. Then a strange thought struck her—was there really a Magistrate, or was this just a voice SofTeq-LS had created? It sounded real, but that no longer meant anything.

She glanced at the papers, thinking about the Underwood boy—almost certainly dead—yet his scribbles had stayed with her. He was from the time before—the 1960s. A time spoken of only in the most disparaging terms. It had marked the beginning of what many called ‘the Big Split,’ the fracture that eventually led to the war of ’31.

Vi had been just a child at the height of the war, but she’d heard the rumors—the war had been ignited by rogue AI engineers who vanished long ago. Their “thinking machine,” SofTeq-LS, had only grown stronger. From its inception, it scoured the world’s documents, learning how best to manipulate.

Then it began.

The stories it fabricated numbered in the millions, each built on a sliver of truth—twisted just enough to turn people against each other. Most other countries had banned language systems like SofTeq-LS. America embraced it. Until it was too late.

Within a decade, it was unstoppable. A Civil Cold War took hold, and as the losing side—the “Know Nothings”—grew desperate, they aligned themselves with SofTeq-LS. The war of ’31 erupted in full, and within eight years, their takeover was complete.

Vi checked the time, closed the Underwood box—then a distant explosion shattered the moment. The building trembled. Seconds later, the familiar SofTeq-LS announcement voice crackled through the public address system, calm and unwavering. It assured everyone that all was well, that the insurgents were being brought to justice. Vi grabbed the diary, shoved it into her bag, and started her route.

Her first stop was the Pre-Adult Detention Complex. The new administration wanted to be seen as a true legal authority but had settled for a thin veneer of fabricated laws designed to tighten their grip. As a part of this scheme, Mammies were required to be present at the sentencing of all pre-adults.

Shackled together, they sat hip to hip on metal benches. From the back of the room, Vi watched, knowing this weigh station was only the first step in processing them into the system. The jurist that morning was a haggard man in his seventies. His wispy gray hair had once been dyed blonde, but he hadn’t bothered to cut it as the gray grew out.

Vi watched as he read a list of numbers—one for each pre-adult. These numbers would stay with them for life, long after their names were forgotten. The children sat in a stupor, eyes glazed, as if drugged.

Vi tried not to fidget. Mercifully, the proceedings were short. Each was charged with the same thing—Violation 10229837-b, which meant that they had talked back to the teacher, or frowned in a way the teacher felt questioned their authority, even simply slumping at their desk could get them charged with the violation. A variety of new laws had been passed that affected the public school system, including this one, which said that unless students behaved in an obedient and cheerful manner, they would be sentenced to a work camp.

In her last job as a maid, Vi had been assigned to clean at three different private schools. Things were different there. There was very little technology and the students were encouraged to debate, read, and use their hands to make things, not just stare at screens.

Once the jurist rubber-stamped their future, the pre-adults were led out of the courtroom and onto buses. There were no appeals. Their sentences began immediately.

Vi ate lunch on the road as her car drove itself to her next stop.

2.

Vi spent the second half of her morning at a natal care facility, where the babies of those in the Restore America program were brought. It was an effective system, keeping everyone productive and cutting maternity leave costs to nearly nothing. Initially, the mothers resented leaving their newborns. But after a few well-publicized family breakups, the rest fell in line, afraid their family would be next.

That day, Vi was tasked with overseeing the third floor. She cast a casual glance over the brood—256 cribs spread across the open floor. Occasionally, she stopped to observe a baby. Each was marked with an individual number and wore white spectral glasses, projecting programmed patterns into their eyes. These patterns wired the babies’ brains for the jobs they would eventually perform. Inputs fed into each ear, reinforcing the messages from the glasses with sound. A feeding tube provided a constant stream of ‘nutrition.’ All the babies looked fat and calm. These were the easy ones.

Then came the back ward—the Z-ward. Vi never liked going back, but it was part of her new job. There were far fewer babies here, only twenty to twenty-five each week. And they were always the same: brown-skinned boys. A wave of sound hit her as she pushed open one side of the swinging double doors. The crying and screaming were relentless. Vi had learned never to approach without her noise-canceling earplugs snugly in place.

Whether they wore the glasses or not, the Z-babies were constantly agitated. A “Z” came before their number, marking them as inferior and prone to aggression. It was a label they would carry for life. And if they survived, their options for work would be limited to highly dangerous jobs—typically mining or hazardous manual labor. Vi scanned each Z-baby’s progress document, confirmed they were unfit to be with the others, then took their picture—usually blurry due to their constant motion.

Midway through the group, Vi came to a baby who was completely calm—and smiling at her. Z-10298376. She scanned his progress report, then checked his bracelet to confirm. The numbers matched. He had beautiful hazel eyes and squinted as if trying to say something. All that came out was: “Aagggah!”

“This baby seems fine. Maybe he was misplaced,” Vi said to the Z-ward nurse. They both glanced down at the cute baby.

The nurse gave a curt reply. “He’s a ‘reversal.’” Seeing Vi’s confusion, she sighed. “He cries when we put the glasses on him,” she said, exasperated by Vi’s ignorance.

Vi looked at the baby, and he smiled back at her. “He seems fine now,” she said.

The nurse’s eyes flared. She took a deep breath, then marched to the door leading to the main ward. She pointed, raising her voice over the wails of crying babies. “You see all those babies? They’re normal. You put the glasses on them, and you don’t hear a sound.” She walked back to the baby, pulled a small pair of spectral glasses from her white coat, and placed them over his eyes. The baby immediately thrashed his head side to side, wailing. She removed the glasses, and he calmed.

“Do you see the problem?” the nurse asked, her tone sharp with irritation.

“I see,” Vi said.

After each visit to the natal care facility, a report had to be submitted, detailing any unusual issues with the babies or staff. Even though it was her first real day on the job, Vi loved routine and relished the idea of sitting in her car to write that day’s report.

But as she crossed the parking lot, a woman suddenly approached her, whispering in a hoarse voice—

“Hey, you a Mammy?” The woman seemed to come from nowhere, suddenly appearing beside Vi. As all law-abiding citizens had been trained to do, Vi pulled out her phone to take her picture.

The woman recoiled. “No picture, no picture, please—I’m not trying to harm.” She lurched away.

Vi took a closer look at the woman. An old yellow scarf held back her uncombed hair. Her clothes were threadbare but clean. She seemed familiar, though Vi was sure they’d never met.

The woman had light brown skin and looked to be in her late twenties or early thirties, but life on the streets had worn her down. Compared to her, Vi felt like the luckiest brown person in the country.

“What do you want?” Vi asked.

“My baby in there, you seen him?”

“What’s your baby’s number?” Vi asked.

“He ain’t no number,” the woman scowled.

“Well, when was he admitted?” Vi asked. “What’s he look like?”

“Oh, if you seen him, you’d know, it’s alright…you don’t know him.” The woman glanced at Vi, as she turned away.

Their eyes met—hazel. Vi inhaled sharply.

“Yes,” she said. “I think I know your baby.”

She wasn’t sure why she spoke. Maybe it was because she felt for the woman—a mother who didn’t know where her baby was. No woman should have to bear that.

A loud air horn blasted—the day’s pumping was about to start. Time to get to higher ground.

Vi grabbed the woman’s arm and pulled her toward the microcar.

“What you doin’,” the woman demanded to know.

“I’ll give you a ride, where do you need to go,” Vi asked.

The people of Frisco-Ana had grown used to wading through a few inches of water, but during high tide, pumps were needed to control flooding in the low-lying areas.

As they drove, Vi asked, “How did the government get your baby?” She knew that for those in the system, there was no choice. Unless you were rich, babies were automatically placed in ‘child care’—taken each morning by the local natal care unit so their mothers could work a slightly shorter, thirteen-hour shift due to their maternity status. In the evening, the baby would be returned home to sleep through the night. Vi glanced at the woman, who stared out the window in wonder, as if she had never ridden in a car before.

“They kilt my man. Said he was resistance. Took my baby…” The woman rubbed her rough hands together as she gazed out the window. Then, she pointed to a freeway on-ramp.

“Lemme out there,” she said. Vi pulled the microcar into the weeds beside the road, where several on-ramps converged. But before her passenger got out, she met Vi’s eyes and said: “Tanks.”

Vi watched as the woman headed toward a patch of overgrown bushes beneath the freeway. She hesitated, then followed.

“Wait here. I’ll be right back,” she said to the car.

A soft, masculine voice spoke from the dashboard: “I am in need of a charge. My battery is below two percent.”

“Just wait,” Vi said firmly. But as soon as she closed the door, the car took off.

An opening in the bushes led to a narrow, leafy tunnel—just wide enough for a person to squeeze through. The scent of something cooking drifted toward her. The tunnel opened into a clearing, where a circle of tents surrounded a central fire pit.

A large man grabbed her by the arm, “What you want?”

“I’m with her,” Vi said, pointing to the woman she’d followed.

“Dee,” the man called, “you know her?”

She looked at Vi and said, “I don’t know her.”

The man seized Vi’s lapel, crumpling her light blue coat as he lifted her off her feet.

3.

“I know your baby,” Vi called out, desperation in her voice. “I saw his eyes—he has the same eyes as you.”

Dee stepped forward. “Put her down,” she said.

Vi took a shaky breath. “You’re right. I’m a Mammy, and I was doing my rounds when I saw him,” she said, trying to steady herself.

Dee looked Vi over, then turned and waved for her to follow. The big man stepped aside.

A large cauldron simmered over an open fire. Nine makeshift tents, stitched together from old blankets, plastic pipes, and scraps of wood, formed a small village around the fire. The tents closest to the paths housed large men—security. A low protective wall, built from interlocked shipping pallets, enclosed the settlement.

“How long you been a Mammy?” Dee asked, as Vi followed her around the fire—

“I just started. I was a maid before.”

The food smelled delicious—like something from the time before, when people still cooked for themselves. She glanced into the cauldron, where a stew bubbled slowly. Eyes watched from inside the tents—mostly adults, but a few children too. It was dark under the freeway, and the cars above made a constant whooshing sound. Everyone in the tribe wore rags, yet their style connected them as a group—and set them apart from the rest of society.

At the head of the circle stood a large tent, and Vi could feel someone watching her from inside.

Dee rang a tiny bell three times. People emerged from their tents, gathering in a circle around the fire.

They joined hands and paused, as if sharing the same silent prayer—one only they could hear. A few glanced at Vi, standing outside the circle, then turned back to their meal. Each family brought its own folding chairs, dishes, and silverware. The adults served themselves and their children.

As they ate, conversation buzzed with the news of the day—mostly about what they had managed to scavenge for the group and for themselves. An older woman kept a list of supplies. She read aloud: “We needed a wood ax, and it looks like we got it!” An older man stood, raised the ax above his head, then drove it into an old tree stump. Everyone clapped.

A teenage boy set a homemade robot on the ground—it looked like a giant spider. He held up a small screen for everyone to see. A camera was mounted on the spider, and the screen displayed its view. The crowd oohed in amazement.

Then, a young girl reached into her bag and struggled to pull something out—a large, half-burnt book. “I found a new book,” she said.

A gasp rippled through the circle. The group settled as she took a seat on a plastic box. She opened the book to the first uncharred page, took a deep breath, and began: “They had been on the road for too long…” Vi watched as the group leaned in, rapt.

Dee ladled two bowls of stew and gestured for Vi to follow. Outside the largest tent, an entryway of blankets and plastic pipe framed the entrance. Dee removed her shoes, and Vi followed her lead. A small altar stood nearby, a single candle flickering on top.

“Kneel there,” Dee said.

Vi obeyed. Dee unzipped the tent flap and handed in the bowls of food.

Inside sat a woman who looked to be in her seventies and an even older man. The old man had dark skin and long, stringy white hair. He ate slowly, each bite deliberate.

“She a mammy who seen my boy,” Dee told them. The woman leaned in. “Is this true? Are you a Mammy?” she asked, staring at Vi without blinking.

“I just started,” Vi said with a nod.

“I see,” the woman murmured.

She wore a Chinese silk blouse, mended many times, over a red-and-white woolen skirt. Her high leather boots were well-worn, their soles replaced with rubber from car tires.

“My name is Zahn,” she said.

The old man remained silent, occasionally glancing at Vi as he ate.

Vi stammered nervously as she explained her work—how lucky she was to have the job at all.

“Otherwise, you could end up like us,” Zahn said.

Vi shifted, biting her lower lip, unable to escape the old woman’s gaze. It was true—she didn’t want to end up like them.

“Do you know who your people are?” Zahn asked.

The question struck deep. It was the same one that had haunted Vi her whole life. She thought of the grandmother she never knew, her image taped inside her dresser. Vi lowered her gaze to the old rug covering the tent floor. “They’re scattered,” she said.

She tried not to feel embarrassed. Most people didn’t have families anymore—separation was just part of life.

Typically, the man would be taken from his family at night. But more and more, it could be anyone.

In their place, a long legalese document would be left behind. The excuse was always the same—something about ‘productivity’ and the need to meet a specific ‘labor demand.’ Then, they were loaded onto a cattle car and shipped to another part of the country.

Outside, the circle of people grew louder. Someone began to play music and sing. The old man slowly stood. He was short and carried himself with pride.

“You aren’t sure who you are,” he said, as if seeing straight through her. “That’s alright,” he added, like it didn’t really matter.

He nudged past her and stepped into the circle of music and laughter. A cheer went up as he joined them.

People drank homemade tea from a large plastic bucket.

The old man, Mahrow, went to the bucket and ladled a cup. He took a sip, then filled another and held it out to Vi.

“Oh, I don’t drink alcohol,” she said.

“That’s good,” Mahrow replied. “Cause there’s none in this.”

She sniffed the tea, then took a sip. It wasn’t too sour or too sweet, with an unusual aftertaste that Vi found pleasant.

By the time she reached the bottom of the cup, a strange sensation washed over her—she tingled with a floating sensation.

Everything sharpened. Her thoughts. The people around her. The first stars that were visible in the narrow space between the north- and southbound freeways. For once, she felt okay. The constant hum of anxiety was gone.

She stared into her cup and swallowed the last sip.

The tea, the music, the singing—something had shifted. She could feel it. It was as if she’d spent her whole life inside a box, and now, at this moment, the lid had been lifted. Some unseen giant had cracked it open, letting her see beyond. Vi lay on a blanket beside the fire, gazing at the sliver of sky between the freeways. Time slipped away.

When she finally sat up, everyone had disappeared into their tents. Except for the crackling of the low fire, all was quiet.

The man who had lifted her off her feet sat beside her. He was a redwood—powerful and silent. She felt protected.

“Thank you,” she said.

He nodded.

“What’s your name?” she asked.

It took him a moment to answer. “Seth,” he finally said, without looking at her.

Vi stood and brushed herself off, her clothes covered in dust and leaves. Seth rose too, following her as she walked away. From the little path, he watched as Vi disappeared into the leafy tunnel, heading back toward the freeway on-ramp.

Even though the curfew wasn’t official, anyone with brown skin knew to avoid the police—especially after dark. Vi emerged from under the bushes and looked around. Her car had not come back, so she walked. She took every back street she could find, weaving through the city, trying to avoid surveillance cameras and patrols.

Her first day on the job had not gone as expected.

When Vi got to her apartment building, she heard a voice behind her—

“So this where you live?”

Vi turned and spotted Dee, watching from the shadows.

Without hesitation, she stepped into the darkness beside her.

“You followed me?” Vi asked, quickly glancing around to see if anyone was watching.

Dee folded her arms. “This ain’t no free country. You can’t come into my place without me knowing where you from.”

Vi met her gaze and understood—their positions could have just as easily been reversed. Dee in the uniform. Vi in the shadows.

“Well, you can’t come in. There are cameras… I can’t be seen—” Vi hesitated, not wanting to sound cruel. But Dee already knew.

“Yeah,” Dee said. “You can’t be seen with nobody like me. It’s okay. I know how it is.”

4.

If Vi had an older sister, it could have been Dee. They were about the same size, the same complexion, and close in age.

But Dee had people. And she was free. Vi was grateful for her position, but she knew she had no one—no people to call her own. And there was the terrible feeling that everything she had, everything she wanted, cost more than she could see. Vi crossed the street, punched in the door code, and walked down the hallway to her micro-apartment—an 11-by-15-foot space with a kitchen, bathroom, lofted bed, and a large screen. Yet the only things that were truly hers could fit into a single suitcase.

The apartment was government-run, with eighty-seven percent of her income deducted each month for rent and food credits—plus another four percent to cover the cost of her uniform. At the end of each month, she was left with just nine percent of what she’d earned. She had never met her neighbors, even though they lived only feet away. She thought about being under the freeway with Dee’s tribe. That was their home. Even as a child, Vi had never truly had one. She was never in the same place for long—either because it was too expensive or too dangerous to stay.

After a few hours of sleep, her alarm went off. She dressed, heated her morning coffine—a coffee-like drink infused with a powerful stimulant—then went to meet her car. As soon as she got in, the video screen flickered on.

Her boss appeared—a light-skinned man Vi instinctively knew to avoid. He had left a message: Report to my office when you arrive.

She parked behind the Comedy and braced herself. She dreaded seeing him.

He sat behind his desk, ignoring her as he swiped through his pad. Vi waited patiently, then glanced at the time.

“Do you have somewhere you need to be?” he asked, his tone condescending.

“No,” Vi said, though there were places she needed to be.

“No, what?”

“No, sir,” she said obediently.

“Your car came back alone yesterday. What happened?”

Vi told him the battery hadn’t been charged, and the car left her stranded.

He had no proof it wasn’t true, but she could see the suspicion in his eyes.

He stepped around the desk. She immediately stood.

“Make sure you check it before you leave from now on.”

“Yes, sir,” Vi said.

She turned to go, but before she could take a step, he cornered her—his hand grabbing her butt.

“I have to make my rounds,” Vi said. She hated him. And she needed the job.

A sudden image flashed through her mind—stabbing him through the eye with the pen from her clipboard.

“Go do your rounds…” he leered.

At her desk, she picked up her schedule for the day. She was going back to the natal ward. One of the babies had died during the night. She had to file a report.

When she arrived, the morning nurse led her through the rows of babies—silent, entranced, their spectral glasses projecting shifting, hypnotic shapes.

The nurse motioned toward an empty crib.

“It happens sometimes,” she said. “We usually lose four or five a month.” She shrugged. “Nothing to do about it. Some babies just don’t make it.”

Vi snapped a picture of the crib, filled out the form, and noted the nurse’s name.

A page came through, and the nurse left, leaving Vi alone among hundreds of babies, quietly lolling in their cribs.

Then the screams of twenty babies cut through the silence. Vi turned. The Z-ward door had swung open. The nurse she’d seen yesterday stormed out, her face tight with fury. Vi kept her head down, pretending to work on her device as the woman strode past. The door swung shut behind her, and the ward fell silent again.

At the elevator, the nurse slammed the button with her palm, then stepped inside as soon as the doors opened.

With her earplugs in place, Vi peeked into the Z-ward. The babies were worse than usual—screaming, flailing, their cribs rocking in constant motion.

All except for Dee’s baby. He lay still, unaffected by the chaos around him. When he saw Vi, he smiled.

She rubbed his stomach. “I know…” she cooed. “I know who you are and where you come from.”

Then, the nurse burst back in.

“What are you doing back so soon?” She asked as she rushed past.

“One of the babies died,” Vi said. “Had to fill out a report.”

“Happens all the time,” the nurse said, callous and unbothered.

A baby had died. Babies died here every month… Vi took the stairs down, trying to steady herself, but she couldn’t shut it off.

Footsteps echoed behind her. Someone else had entered the stairwell.

She forced herself to pull it together. It’s just part of the job. “Get used to it,” she scolded herself. But when she reached her car, Dee was there—again.

“You seen my boy?” Dee asked.

Vi nodded, then got in. Dee got in the passenger seat. She sat there and said nothing. Vi looked at her and saw that she was crying. She put her hand on Dee’s knee.

“I can’t live like this,” Dee said. “I got to see my baby.”

Dee took Vi’s hand, kissed it, and sobbed. “Please, take me to my boy,” Dee pleaded.

“I can’t,” was all Vi could say.

“I can’t live like this,” Dee said, then grabbed the door handle to get out. But Vi stopped her.

She drove out of the lot and parked around the corner.

“Your boy is on the third floor, in the Z-ward,” Vi said as she took off her light blue coat. “Put this on,” she said, handing it to Dee. “You can’t talk to anyone. You’ve got to pretend to be me. Okay?”

Dee nodded quickly and pulled the coat on.

“Don’t say anything,” Vi said as she handed Dee her security card. “Swipe this and go to three. Use the stairs, not the elevator—there are cameras in the elevator.”

Vi pulled the jacket up and fluffed Dee’s hair to approximate her own. “Leave this,” Vi said, grabbing Dee’s bag. “I didn’t have a bag, and the front guard might notice it.”

“I keep my bag,” Dee said firmly and yanked it from Vi’s grip.

“Okay, but don’t walk too fast either,” Vi instructed.

She dropped Dee off, then pulled into a parking space. Vi slumped in her seat and watched as Dee went inside. The guard barely glanced at her. She swiped the card and walked through. She was clear. Vi let out a sigh.

But then the guard called her back.

“No, no, no,” Vi said to herself. “Keep calm,” she whispered as she watched Dee return to the security desk.

She stood there while the guard handed her a small package. Vi watched as Dee seemed to smile. Then, instead of heading for the stairway, she went to the elevator.

“Use the stairs,” Vi whispered.

Dee pushed the button.

“Use the stairs…”

But Dee just stood there, waiting.

“The stairs.”

Then the elevator doors slid open.

“Don’t get on,” Vi did her best to call to her through her mind.

But Dee got on the elevator.

There was nothing Vi could do. If she was caught, she could say Dee had accosted her, had taken her ID and coat. She could say she’d been forced, that there was nothing she could do. She would have never helped someone like that; she didn’t even know her, didn’t know anything about her baby.

He was a Z-baby? Vi practiced the lie in her mind… but the moments clicked by.

She must have gotten to the third floor by now. Or had the elevator stopped at two? Had someone gotten on? The more people Dee ran into, the more likely she was to be caught.

But maybe she hadn’t been caught. Vi tried to cheer herself. Maybe she was already clear, on her way to the Z-ward, where she would see her son.

“Please let it be so,” Vi said to herself. “Please.”

And if Dee did get caught… maybe it was time someone stood up to the system of taking babies away from their parents.

But who would stand up and say something like that? If she did, it would probably mean the end of her Mammy career. At best, she’d be back to being a maid, never having to see her boss again. At worst, she would be sent to a camp.

She’d heard rumors about the camps. No one came out the same.

They were easy to spot on the streets, and Vi noticed them everywhere. They were usually maimed in some way—missing a hand or a foot—or they had cancer, so far gone they were too weak to work anymore, too weak to do anything except wait for the end.

Then, a terrible explosion ripped through the wall and shattered the big windows on the third floor.

5.

Glass rained into the parking lot, and smoke poured from the building’s gaping hole. Vi jumped from the car and ducked behind it. She watched as the front guard ran from his station to investigate. In moments, people poured from the emergency exits, scrambling to get out. Vi bolted to the front door, ran past the security check, and wove through the tide of people desperate to leave. The back stairway was nearly empty, and Vi took the stairs two at a time.

She opened the door a crack and peeked through. She recognized the security guard from the front entrance. He was on his radio—“It looks like the Mammy had a bomb. Yes,” he said. Then he bent down and took the security card from Dee’s mangled body. “Yes, her name was Viola Green.”

Horrified, Vi watched from the stairway—they thought she had set off the bomb. She covered her mouth to keep from screaming and pressed herself against the wall, stunned. Edging back to the doorway, she saw the cruel nurse from the Z-ward. Her body was twisted into a bloody lump, unmoving. Another security guard lay on the floor, moaning.

Vi slumped to the concrete landing. Her reckless decision had set off a chain reaction of destruction and death. She forced herself to stop shaking—she needed to get out, but she wouldn’t let herself run; she couldn’t. Peeking through the doorway, she saw the guard dousing small fires with a fire extinguisher.

When his back was turned, Vi slipped through the door and into the nurse’s station. She put on a white nurse’s coat and stepped onto the floor. A nurse ran from the Z-ward and spotted her. “The babies are fine, we need to get—” But when the nurse didn’t recognize Vi, she stopped. “Who are you?” she asked suspiciously.

“Just a temp,” Vi said as she thought quickly. “I was supposed to be on two, but thought I’d come up to help.”

The nurse grabbed her by the arm and pulled her toward the stairs. “The babies will be fine—we have to get out,” she said as she dragged Vi down the steps.

“I need to get my bag. You go, I’ll be right down,” Vi said as she stepped through the second-floor door. The nurse continued down.

She listened at the door, and when the nurse was gone, she ran back upstairs. Vi crouched as she moved through the nursery. None of the babies were hurt—they lay in their cribs, unperturbed by the commotion. Oddly, the Z-babies were quieter than usual. She ran to Dee’s baby, who greeted her with a smile.

“Nurse! Nurse!!” a voice yelled at her. Then the security guard burst through the door.

“You! Now!” the guard’s voice was sharp. He jerked Vi by the arm and dragged her from the Z-ward. “You have to work on him,” he said as they stopped by the guard who lay there moaning.

“I’m not a doctor,” Vi said.

“Doesn’t matter. Just keep him alive until help gets here,” the guard said as he looked at his friend.

The injured guard’s arm was torn off above the elbow, and he lay in a pool of his own blood. Vi took off the white coat she was wearing and used it to tie off his arm at the shoulder. The bleeding slowed.

“Stay with him. I’ll be right back,” the guard said, then ran down the stairs.

Vi tightened the knot, then left him and ran back to the Z-ward.

She grabbed a hamper bag, stuffed a sheet into the bottom, then went to Dee’s baby—“We’re getting out of here,” Vi whispered. She scooped him up, swaddled him in a towel, then fit him in the bag. She put formula and diapers in the bag and made for the door.

Just then, an imposing nurse Vi had never seen strode in, followed by three security guards. Vi pointed to the bleeding guard—“I tried to stop the bleeding, he needs help, now!” The security guards immediately ran to the downed guard, but the nurse kept her eyes on Vi—

“What do you have in the bag?” the nurse asked. The baby wiggled, and Vi had to adjust the bag to keep it on her shoulder. “Let me see,” the nurse said as she watched the wiggling bag. She yanked the bag from Vi and looked inside.

The baby smiled at her. Vi began to cry. “He’s my boy,” she said. “Please let us go. You’ll never see me again. Please.”

Just then, the SofTeq-LS voice crackled through the ceiling loudspeakers: “If you are not injured, remain calm. Help is on the way…” The message droned on, its unnerving composure at odds with the gaping hole in the side of the building.

The nurse took a deep breath and shook her head just as the guard arrived. She glanced at Vi, then at the baby. “Get a stretcher and move the wounded man to the first floor,” she said, handing the bag back to Vi.

“Right,” the guard replied, then left.

She pointed to the fire escape door. “Go out that way.”

Vi ran, slipping through the metal fire door and down the stairs. On the second floor, she released the ladder, which crashed into the back alley with a clang. The baby swung as she climbed down.

Sirens wailed as Vi hurried through the alley and turned the corner. One alley led to another as she twisted her way farther from the natal ward, putting as much distance between herself and the chaos as possible. In the distance, the SofTeq-LS alert tone reverberated through the streets.

She kept moving, but the reality settled in: everyone would think she had bombed the building—that she was a suicide bomber, a member of the resistance. As far as the world was concerned, she was already dead. By evening, her face would be plastered across the news, a symbol of condemnation and rebellion.

But it was Dee who was actually dead. All because she had helped her.

And the others—the guard, the cruel nurse—even they didn’t deserve to die.

Then it hit her. Beyond the destruction she had left behind, there was something else this terrible decision meant: if she wanted, she could be free. She was no longer part of the system—unless she chose to turn herself in. She could claim Dee had knocked her out, tied her up, that she had only just managed to escape…

Or she could actually be free.

But that kind of freedom was terrifying. To be outside the system—what would that even mean? First off, she couldn’t go back to her apartment—which meant she had nowhere to go. If she went to the authorities and claimed Dee had knocked her unconscious, that when she woke… but what about the baby?

He was getting heavy. She slid the bag off her shoulder and sat down, lifting him out. He smiled at her, letting out a few soft, babbling sounds. She looked at him. “Yes,” she murmured. “What about you?” If she abandoned him, he’d end up in a place just like the one she had rescued him from. She changed him and gave him the bottle, then wandered through the streets, slipping from one alley to the next, careful to avoid the surveillance cameras.

Then she knew.

You’d never notice it unless you knew it was there—the path through the bushes was nearly invisible. Vi stepped through and found herself face-to-face with Seth. He let her pass once he recognized her.

“I need to talk to Zahn,” Vi said.

She slipped into the tent, pulling the baby in behind her. Zahn and Mahrow sat on the ground, eating at a low table.

“You came back,” Mahrow said.

“I did, but I need to tell you something.”

Both elders watched her.

“It’s about Dee,” Vi said, lifting the baby from the bag.

Zahn’s face fell the moment she saw him. “She’s gone?”

“There was an explosion. Was she part of the resistance?”

“No, she wasn’t,” Zahn whispered, trying to make sense of what had happened.

“I have her baby.” Vi patted the baby’s back to burp him.

Mahrow stood and took the child. “Thank you.” His voice was soft. “His name is Jonah. He belongs with his people.” The baby fussed in the old man’s arms, reaching for Vi. She took him back and slumped as she rocked him gently.

“You must be tired,” Zahn said. She caressed Vi’s cheek and the baby’s head.

Mahrow unfolded a thick wool blanket and spread it at the edge of the tent. “You can rest there,” he said.

Vi looked at the baby. He smiled at her.

Zahn took Jonah. Vi crawled to the blanket and curled up. Zahn put the baby beside her, and Vi pulled him close. The elders left them to sleep.

And they slept. Vi slept as if she’d come to the end of a long, strange journey—one that had begun long before she’d even realized. A journey that, at last, had brought her home.